In the very centre of the Mediterranean, the tiny Republic of Malta is formed by the three main islands of Malta, Gozo and Comino. Due to its strategic location, the Maltese archipelago was colonized by one world power after another, witnessing the rise and fall of many kingdoms and empires.

The island nation with its impressive fortresses, ancient temples, and rich traditions boasts an eclectic mix of influences to its culture and language. Malta is steeped in history – a history with a long tradition of Jewish presence.

Jewish Settlement on Malta

Jewish settlement on Malta can be traced back to Phoenician times, to approximately 900 years BCE. In the inner apse of the southern temple in Ggantija in Xaghra, there was found an inscription in the Phoenician alphabet saying “To the love of Our Father YHVH.” It is believed to have been made by the Jews, possibly of the tribes of Asher or Gad, who had settled the islands with the Phoenicians. Both the Hebrew and the Phoenician languages at the time were Semitic tongues closely related to one another.

Probably the most famous Jewish visitor to the Maltese islands was none other than Apostle Paul, who in 60 CE, on his way to Rome, was shipwrecked on Malta. According to the Acts of the Apostles, he converted many of the local inhabitants to Christianity during his 3-month stay, thus beginning a new chapter in Maltese history.

Many Jews had found a home on the islands throughout the centuries. Notably, the catacombs in Rabat on Malta show that a number of Jews lived on the island during the fourth and the fifth centuries. Furthermore, contemporary records show that under Norman rule in 1091, a total of 500 Jews lived on the main island of Malta and 350 on Gozo. Prior to 1492, the city of Mdina in Malta had been one-quarter to one-third Jewish.

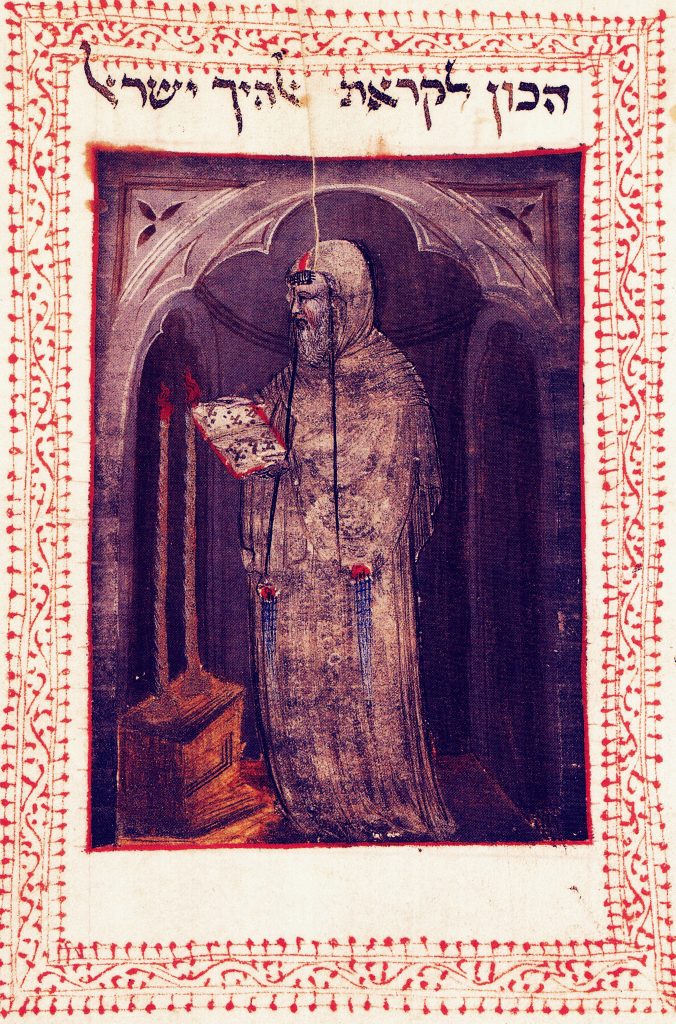

Abraham Abulafia

In the 13th century, the windblown rocky island of Comino became home to an exiled kabbalist Abraham Abulafia, the founder of the school of prophetic Kabbalah. A self-proclaimed messiah, he was ostracized for working with the creative powers of the Divine Name, which was considered a form of white magic. The rabbinical consensus was that such application of Kabbalah should be prohibited. Exiled for his controversial practices, Abulafia is believed to have spent his last years as an hermit in a cave on Comino, and to have died on the island.

Abulafia became famous for trying to convert a Catholic Pope to his version of Judaism. In 1280, he set out for Rome from Capua in order to convert Pope Nicholas III. When the Pope heard of this, he ordered to “burn the fanatic at the stake”, which was promptly prepared outside the Pope’s summer residence. However, the Pope died of a stroke the night before Abulafia had reached him. The troublesome kabbalist was imprisoned for a few weeks but was subsequently released.

Despite his controversial statements and practices, Abulafia is believed to have been an inspiration for latter Jewish sects that emphasized devotional practices and communion with the Divine. He was an avid traveler and had visited Jerusalem, a dangerous pilgrimage at the time. In his spirituality, he was influenced both by St Francis of Assisi and the Sufi masters of the Middle East, and ultimately believed the communion with the Divine transcends the boundaries of any religion.

The Spanish Edict of Expulsion

The Jews on Malta, unlike in most other European countries, never lived in ghettos, although an unsuccessful attempt was made in 1458 to restrict the Jews to a special quarter. They were free men who engaged in business, trade and commerce, and several Jews even owned slaves. This situation changed dramatically after the edict of expulsion of Jews from Spain, and the subsequent arrival of the Knights of St John.

The edict of expulsion forced all Jews to leave Spain in 1492. As Malta was at the time under the Spanish rule, this applied to Maltese Jews, as well. The Royal Council tried to argue that Malta was a special case since the expulsion of the Jews would radically reduce the archipelago’s total population – an argument that highlights the significance of the Jewish presence at the time. However, this had only resulted in the Jews being required to compensate the Spanish crown for the cost of their own expulsion.

Many of the Jews appear to have converted to Christianity after the edict in order to stay, which is further evidenced by a large number of Maltese surnames with Jewish origins. However, the Jewish connection was lost with time and remains for the most part unknown to the bearers of those surnames.

The Knights of St John

In 1531 any remaining Jews faced expulsion from Malta as one of the conditions of the Knights of St John receiving the island. Both Jews and Muslims were thrown into prison, as the mandate of the knights was to free the Kingdom of Sicily, which Malta was a part of, from any heretical influence. Many non-Christian families had chosen to convert and adopt Christian customs.

During the time of the knights Malta became notorious in the Jewish world as one of the “four kingdoms of ungodliness,” because of the slave trade that the knights engaged in to back their military pursuits and building projects. At the time of the knights, the only Jews who lived on the islands appear to have been slaves.

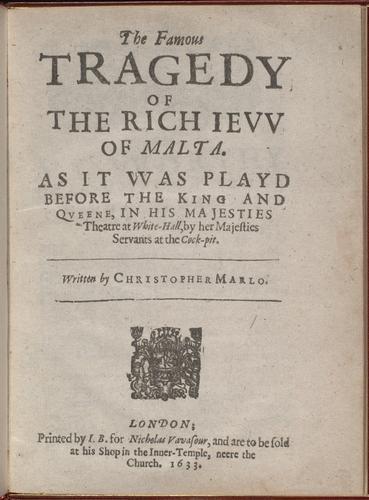

Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta, set at the time of the Great Siege of 1565, portrays a Jew as a plotting murderous character, who conspires with the Turks to besiege the city he lives in. The play, which possibly inspired Shakespeare to write his Merchant of Venice, is a vivid display of contemporary prejudice and conspiracy theories postulating that the Jews financed the Ottoman siege of Malta in 1565.

In the 18th century, a certain Joseph Cohen, a slave who was a tavern keeper in Valletta, and a convert from Judaism to Christianity, prevented a plot by the recently captured Pasha of Rhodes to overthrow the Knights of St John. He overheard Muslim slaves conspiring to murder the Grand Master of the order, obtained an audience with him and informed him of the conspiracy. Over a hundred slaves were executed upon discovery of the plot. For his loyalty, Cohen was set free and granted a house, Monte di Pieta in Merchants street, Valletta.

Jewish Presence in Modern Times

After Napoleon banished the knights and abolished slavery on Malta in 1792, several Jewish settlers arrived from North Africa and the Mediterranean, but the Jewish community on the islands never reached its pre-expulsion size. From the beginning of the 19th century it rarely exceeded fifty members.

During WWII, Malta was the only European country which did not require visas for the Jews fleeing Nazi persecution. Several have made their home in Malta in the 1930s and fought with the British Army.

Today, Malta’s tiny Jewish community numbers approximately 100, and has a Chabad house with its own synagogue, and another synagogue in a residential building in Ta’Xbiex, walking distance from the city of Sliema. Next to the Chabad house is the only kosher restaurant in the islands, L’Chaim, serving Jewish Israeli cuisine.